Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

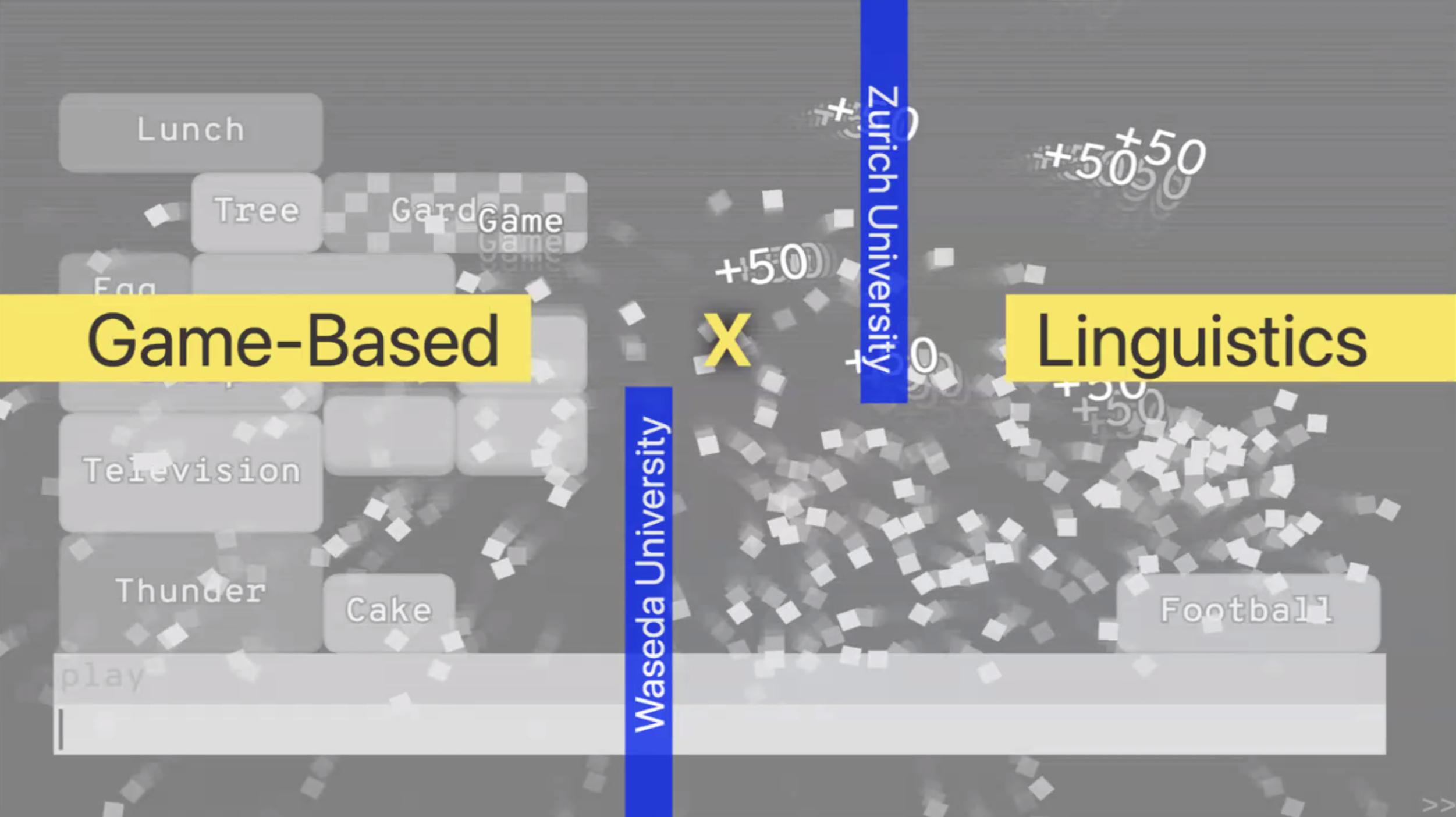

Thi research project, funded by the Leading House Asia: 2024 Call for Consolidation Grant and led by Prof. Dr. Noah Bubenhofer (UZH) and Prof. Dr. Joachim Scharloth (Waseda University) takes the similarities between digital language games and linguistic research processes as a starting point for analyzing the processes involved in the creation of spatial metaphors. The aim is

to reveal typical strategies for translating cognitive concepts and statistical relations into spatial metaphors,

to examine the significance of spatial metaphors for the construction of both research objects as well as learning objectives, and

to develop a best practice that guides a reflexive and critical translation process.

We will apply this to two domains of linguistic pragmatics that have so far been underrepresented in both game development and data-driven language analysis:

sequentiality of utterances in the interaction, and

stylistic variation

Computer games are an increasingly popular as well as complex medium: they allow interaction in virtual spaces and combine this with storytelling or challenges to skills. Increasingly computer games are also being designed as "serious games" or used for educational purposes. One important field is game-based language learning, in which gamification elements and games are used to foster the development of linguistic skills.

In gamification, this can take a very simple form, for example when points are earned while learning vocabulary, creating a competition between several learners. However, it is more challenging to develop video games that use game mechanics to create a contextual link to the learning objectives. This is the game-based learning approach. Here, procedural rhetoric is used to support the emergence of concepts, which are related to the learning objective, while playing (Scharloth 2024; Scharloth & Deissler). One example is learning syntax rules by playing a shunting game in which the wagons of a train, which stand for sentence elements, have to be placed in the correct order (Scharloth 2024). In order to become playable, certain aspects of language have to be translated into spatial metaphors.

Data-driven linguistic research also makes use of spatial metaphors in many respects. It relies on visualizations in which structures can be made visible in large amounts of data. Classical visualizations of language such as collocation graphs use spatial metaphors which depict the statistically significant semantic proximity of words (Bubenhofer 2020). And it even uses spatial metaphors at the level of fundamental theoretical concepts, e.g. the vectorization of meaning leads to the calculation of a semantic space (Mikolov et al. 2013; Lenci 2018; Bubenhofer 2018). The research process also has a playful character: as in a game loop, researchers constantly produce new results by changing parameters or adding data based on their interpretation of visual output resulting from the translation of complex statistical relations into visual metaphors. And the explorative visualizations produced by researchers are also increasingly interactive.

Digital spaces allow for a wider spatialization of language. Language normally appears to us in text form, i.e. sequentially. However, language is inherently multidimensional: although syntagmatic concatenation is important, it is based on paradigmatic orders that are relevant for the organization of semantic space (synonyms, antonyms), but also for morphosyntactic organization (verb paradigm: conjugation; noun paradigm: declination, etc.). In addition, digital space enables the dialogicity of language and its pragmatic dimension to be represented.

If such forms are to be found, fundamental research must be carried out into how different aspects of language can be represented in a digital, interactive space (Bauer & Kato 2018).

By exploring the spatialization of language in the digital, interactive space from a ludic and corpus linguistic perspective we aim at developing principles for game design for language learning (1.), for improving the exploratory potential of interactive visualizations in data-driven linguistic analysis (2.), and expand the scope of interactive visualizations to include pragma- linguistic dimensions (3.)

Game-oriented pedagogy is based on the assumption that design elements and activity patterns of games trigger emotions such as curiosity, joy or frustration. These emotions in turn act as a reward or incentive for the playing subject to continue playing and thus to engage more deeply with the learning object (cf. Buckley / Doyle 2014: 1162f). The high prevalence of language learning apps has given the discussion about gamification in foreign language learning a special dimension. The unifying element of research in the field of game- based learning is the search for universal design elements that lead to an increase in motivation and desired behavior in an abstract context. Preferably, experimental research designs are used to systematically investigate the effectiveness of individual game elements in supporting learners (cf. Ofosu-Ampong 2020: 128). This can also be seen in the practice of digital language learning: Govender & Arnedo-Moreno (2020) show in their study that all of the 20 language learning apps they examined contain gamifying elements. Four of these apps even made use of more than 20 gamifying elements in very different contexts.

With Bogost (2015), we want to show that a focus on individual game elements misjudges the character and richness of the medium of games and can even lead to alienation from the game as a medium for discovering and appropriating reality in the medium term. Rather, language learning games must model relevant aspects of the respective linguistic learning object through the targeted selection of rules, components and mechanics in order to enable noticing and subsequently also understanding. Of course, this means that there can be no universal game components, game mechanics and dynamics that are equally suitable for all aspects of language learning. On the contrary, every aspect of language that is to be conveyed requires specific modeling through the means of procedural rhetoric.

Spatial metaphors play a central role here. By developing principles for translating linguistic concepts into elements of procedural rhetoric, we aim to guide and support this change of perspective from single design elements to procedural rhetoric.

Linguistic visualizations are mostly static representations of analysis results. And even where interactive, explorative visualizations are used in data-driven analyses, they are usually based on static models. Instead of static visualization, we will develop the principles of a ludic exploration of data that enables the emergence of alternative concepts.

By tackling pragmatic and stylistic appropriateness, the project highlights how language varies depending on context and social interactions. Data-driven corpus linguistics has only developed few static solutions for visualizing stylistic and pragmatic variation. Equally, language learning games tend to focus primarily on vocabulary and grammar, areas that are essential but only a part of language mastery. This project seeks to go beyond these basic elements by applying the newly developed best practice to games and corpus studies that address pragmatic appropriateness, and stylistic variation. These areas reflect the nuances of real-world language use and are crucial for learners aiming to achieve a deeper and more functional understanding of language. And they are equally challenging for data-driven linguistic analysis, if it wants to avoid the mistakes of a static structuralist perspective. Developing spatial metaphors that allow for an interactive approach to analyzing and learning pragma-linguistic dimension is a challenging and innovative test case that goes beyond traditional forms of visual representation.

| Team Tokyo | Team Zurich |

|---|---|

|

Prof. Dr. Joachim Scharloth Prof. Dr. Bryan Hikari Hartzheim Prof. Dr. Sylvain Detey Prof. Dr. Judy Wang M.A. Jie Yang |

Prof. Dr. Noah Bubenhofer Dr. Hiloko Kato Dr. Daniel Knuchel M.A. Xenia Bojarski M.A. Maaike Kellenberger M.A. Davide Ventre B.A. Sonja Huber |